What do some of the world’s most transformative thinkers do differently? Can anyone learn to be creative? What role does technology play in the creative process? Dr. Alana Ackerson, a serial entrepreneur, investor and theologian, tackles these subjects and more in her new book, Creative Humans: How Technology Is Transforming Human Nature and Future Possibility.

Where We’re Headed: Insights from the CI Investment Team

On the cusp of 2025, four senior investors answer questions about the year ahead. Given its ability to analyze large amounts of data, identify patterns, automate tasks and improve efficiencies, it should come as no surprise that artificial intelligence will play a prominent role in the deals that CI is looking into.

Five Tips to Help You Find Your Next Great Hire

As members of the Human Capital Services Team for Connecticut Innovations, Bo Bradstreet and Marina DeThomas help CI’s portfolio companies find exceptional candidates to fill key roles. We asked Bradstreet, who also serves as managing director of Guilford-based Bohan and Bradstreet, a firm that was recognized by Forbes as one of America’s Best Recruiters—Executive Search five years in a row, for recruiting advice. Read on for his best tips.

Founder Spotlight: Eric Rosow

When we last sat down with Eric for our founder spotlight, he was solving “clinical data disorder” with his team at Diameter Health, a digital health company he co-founded in 2013. The company was acquired in 2022, but Eric hasn’t slowed down. Writer Amy Hourigan got the scoop on his latest venture, Conduce Health.

Thinking About a Rebrand? We’ve Got You Covered

Your customers, your prospects, your employees and your investors want to know what your company stands for. Branding helps you achieve that goal. But what if something shifts? Here’s how one venture-backed company is tackling a rebrand, along with expert advice if you’re considering one yourself.

Founder Spotlight: Dr. Reid Waldman

When we first spoke with Reid Waldman, M.D., his company, Veradermics, was developing a revolutionary new treatment for common warts. Writer Amy Hourigan sat down with the dermatologist and founder to get an update about the treatment’s progress and ask about the other first-in-class candidates in the company’s pipeline.

Founder Spotlight: Bill Moschella Sold His Startup Just Three Years After Launch. Here’s His Hard-Won Advice.

Serial entrepreneur Bill Moschella’s company, Populi, was acquired by Definitive Healthcare for $52 million just three years after inception. Here, he tells writer Amy Hourigan how the company got its start, why he decided to sell, and the mistakes he hopes other entrepreneurs will avoid.

Amy Hourigan: Thanks for talking with me, Bill. You went to school for music. How did you find yourself at the helm of a digital health company?

Bill Moschella: I went to a couple of different music schools to study 20th-century music theory and composition, which is technical, math-type stuff, but since I can read music, I also played in multiple bands. It was fun, but I wasn’t making any money. Sometime in the ’90s I bought a digital recording studio and realized I could make money recording bands, which, at the time, was kind of groundbreaking. I got really into it and started connecting with people in tech support—back then it was mostly by telephone—asking questions and learning how to fix things while providing feedback about the product. This was the buildup to everything I would later do with software.

Eventually, someone at the company connected me with someone else who they thought would be interested in learning how I was using their software. I got free access to their application and started using it to transfer music by converting digital stored music into digital shared music. This was during the early days of Napster and music sharing. I found ways to reduce file size and maintain quality.

AH: That’s impressive for someone who is self-taught.

BM: Well, I’m not some genius. I was just spending a lot of time on it. I figured out a bunch of cool hacks and started writing about them. At the time, everything was really slow, but everybody wanted to have these animated splash images on their websites or animations with video or audio. I figured out a way to compress the audio to get the most out of it. The company liked what I was doing and eventually put me in touch with a big publishing company, IDG Publications, which offered me what was at the time for me a lot of money to write about what I was doing. I ended up writing a couple chapters in these large tutorial books for several years.

AH: So digital music led you to programming?

BM: Yes. And then I bumped into somebody who had an advertising business who needed help writing TV commercials and radio jingles. He had an advertising background. And I had a technical background, but it turns out I also had innate sales skills that I didn’t know I had. Early on, when we were doing radio commercials, I had to try to find businesses that had crappy ads, so I would listen to the radio all day long, going through four or five stations at a time. I started learning who was in the rotations. I made a gigantic list on a yellow notepad, and then I went to the Yellow Pages and just started calling companies on the corded wall phone at my parents’ house. When I got meetings with people I said, “Hey, if we make your radio commercial better will you give us the advertising component as well—the strategy, the media buying and planning, etc.?” Besides sales, I found I was good at negotiating rates and understanding where to buy remnant inventory.

AH: So that business took off?

BM: Yes, the business took off and I was able to pay myself. At some point, I wanted to grow even bigger, but my business partner didn’t. This was during the dot-com boom. I knew a few people in the local banking industry, and so I asked them how to buy somebody out. I had no idea how to do it. On their advice I called different boutique banks in in New York, and they were like, “Oh, great, you’re in a technology business. You want a loan?” They gave me a gigantic loan! I couldn’t believe it. My business partner couldn’t believe it. I bought the company from him and quadrupled the size of the business in a very short time.

AH: Sounds like you rode the dot-com boom.

BM: I did. I got into software development, ERP, CRM, digital marketing, email marketing; we became a full-service digital agency. But there were bigger versions of that happening all over. Fortunately, I saw an opportunity to tie it together by doing marketing, digital marketing, marketing automation and downstream ROI analysis. The business evolved into a financial-planning-and-analysis-meets-marketing company. Around 2009 to 2011 there was a big movement around marketing automation, which became demand generation. The space got crowded and I realized I wasn’t going to make it. I couldn’t compete with the really big firms that were popping up.

AH: Is that when you turned to digital health?

BM: Right. At the time, the only industry nobody gave a hoot about was the provider market. So I said all right, let’s turn this into a digital marketing business for providers. And that was the beginning of going out and raising capital, getting into investment banking, dealing with venture capital, having to learn the ropes of running sales, marketing, HR, customer service, accounting and forecasting. I had board members and investors. It was a crash course. It was the best and worst experience I ever had because there were a lot of ups and downs. It was brutal working with sophisticated investors who had a lot of money on the table and realizing just how much more there was to building a successful business. That was 2018. Everything changed from there. [Moschella’s company, Evariant, was acquired in 2020.—ed.]

AH: What a great story! So Populi focuses exclusively on providers?

BM: Yes. There’s a huge business in care delivery and coordination and the whole clinical piece. But then there’s the business of running the business, which not all health systems do as well as maybe they could. Those who are doing it well succeed because they treat the health system as a business.

If these organizations want to grow, they need to make certain decisions so they can stay in business and continue to deliver good care. Populi can help with those decisions. We can help you recruit physicians, understand whom to merge with or acquire, figure out the demand for a particular service or therapy in an outpatient or inpatient setting, whether you should be entering into a value-based contract, etc. There’s lots of data out there.

AH: And you’ve figured out how to put that data to work?

BM: I understand data science and data engineering. That’s where a lot of people fall down.

AH: Your website says that Populi delivers analytics in platforms that your customers actually work in, which seems like a simple concept. Why was no one else doing it?

BM: Why? Well, let’s take a step back. The old-school methodology of delivering this type of service was sending people a bunch of data they could use as they pleased. The other was creating a product people could log in to. Here’s why that doesn’t work. If a provider doesn’t have the money and the resources to manage the data and build their own product, even if they say they want to do it themselves, they’re typically not going to. So that’s a failed approach and you’ll churn that customer. Those who do create the product typically end up saying something like how they can’t get to the answer because they want to double click on your explanation of, say, what you think valve replacement is and look at all the procedure codes and look longitudinally…but we didn’t build it that way. Another failed approach. So I said to my co-founder, Nathan Salmon, “Here’s the deal. Here’s all the data, I know how to get it, here’s the product concepts. I can run the business. But you have to build something that’s plug-and-play from day one. Put your credit card in, get a user license, start using it. It’s got to be very modular and connector-based so people can use the data in Salesforce or Tableau or Google or Amazon.” That’s how we bring analytics to the platforms customers live and work in every day.

Ten years ago, people didn’t know that some of these platforms existed, or if they did, they couldn’t afford them. Now they’re commonplace. What’s not commonplace is an ecosystem in a marketplace where you can tap into these highly complex and HIPAA-compliant analytics with de-identified patient information. You can’t get into the business of data without also being in the business of compliance and security. You also need to understand the controls and policies that are involved with a larger team as it scales. I teed up this opportunity for us to get very narrowly focused on an industry with a key set of business problems and the data that was required to answer those problems, and one that had massive gaps of why they couldn’t consume and use the data. We hyper-focused. That’s why the company was bought so quickly.

AH: How did the deal come about?

BM: It was kind of haphazard. I’m always trying to acquire data assets. One of my angel investors knew I was looking for data and recommended I talk to the corporate dev folks at Definitive. I had an initial call and said, “Hey, can I buy your data?” They said, “Can we buy you?” I told them the company wasn’t for sale, but I said we’d consider it. After one or two meetings they realized acquiring us would be a great way to get the vertical expertise they were looking for, so we kept talking. Those processes aren’t fun, and we had our moments. You always do because it just gets tough. But they were great to work with, which to me was another test. You wonder what it will be like if you disagree on something. They were rational and reasonable and fair. And that’s all you can really ask for.

AH: How did you know it was the right time to sell?

BM: The answer is not just because the price was right. Because, if you’re an entrepreneur, is the price ever really right?

AH: And it’s your baby, right?

BM: Yeah. It’s your baby, and you wouldn’t be an entrepreneur if you didn’t think that no matter what number someone put in front of you that you couldn’t get more. You have your good and evil conscience speaking to you. “Don’t take it. You can do better.” And then there’s the other part that’s like, “Dude, go do something else.” Maybe there’s also a VC whispering in your ear about the returns.

We didn’t have a lot of investors or board members at Populi. It was Nathan and me, so it was an easy conversation. We just sat down and talked about what we wanted out of life and what a good outcome would look like, and not just in terms of money. There were three or four things that were important to us.

I knew that the founder and the chairman of Definitive were good people and experienced leaders who know healthcare. I was able to let my business partner know that these people are ethical and they’ve run companies we would enjoy working with and for. That was the first opening of the door.

The second had to do with our employees. I’ve been part of a handful of companies where the employees got screwed. The story goes something like this: You have a great idea. Maybe you’re a single entrepreneur, maybe you’ve got a partner. At some point your cost basis common stock, which is fantastic, it’s got nothing but upside. It starts getting stack ranked and venture capital comes in and then there are notes and Series A, B and C rounds and different preferences and waterfall payouts and strike prices and all sorts of complicated stuff. Most people don’t understand what they’re getting into. They could receive an on-paper value of a whole lot of stock. But what they may not know is what it will take to get over the strike price. And then how much value is going to be over that? And are we going to hit different preference levels? Is anybody going to get paid at all, including the founders?

I’ve been in situations where—and this is just capitalism—you couldn’t have gotten to where you did if you didn’t take money. So how do you manage and negotiate capital? A lot of people don’t understand it, so they get taken advantage of. Even if you know what you’re doing, the market demands what it demands at any given point in time. If valuations are down and you need money, you’re in a rough spot. You could be in a down round, you could be in a flat round, you could be in a decent round, but you could be accepting terms that might not be all that great. And eventually there’s voting and preference and waterfall and payout. And there’s what happens when you actually sell the company. I’ve seen some awesome numbers on the top that yield zero or negative for employees because the sale price in this common stock price is underneath the strike price they were given. These situations have put large groups of people I’ve known in a lousy position. And then as they go on to a new company, there are economies of scale and integration exercises.

It’s just business, but having had those experiences and having brought a lot of people into the company where the majority of the capital came from my wife and me and a handful of folks like Connecticut Innovations, who I have a great amount of respect for, and Millennium out of New York, and a couple of angels who brought a lot of value to the table due to their industry expertise, we were able to have a very open, transparent conversation about what we were going to do and how we would go about it. We converted nothing to stock. Everything was in a convertible note. That meant the control stayed with Nathan and me the entire time. I treated every note holder as a board member, though. I asked for their input. There was a lot of conversation. The investors had to be taken care of because we all stepped up and put money in, and I was crystal clear that the employees needed to be taken care of as well. If the acquirer says investors are going to get paid but we’re going to kick the tires on everybody else, the answer’s no. Everybody’s got to come over minus a few folks on the HR and finance side who we’d already talked to.

We were only interested in selling to the right company with the right leaders who had the right mindset and vision for the company. Definitive acquired us because they needed product and more subject matter expertise. We needed scale. But we already held a lot of the same values and principles. It was just a cool culture we were joining, which isn’t usually what happens.

AH: How long did the process take?

BM: Well, Definitive had to go through their due diligence, which isn’t easy. In fact, with a company like ours, it’s harder because there are more unknowns—I don’t have 10 years of historicals. There was a leap of faith on both sides. The process took six or seven months.

AH: Do you have advice for other founders who are considering an exit? Sounds like you have learned some lessons over the years.

BM: Yeah, I’ve had a couple exits. Some were anticlimactic. Some I didn’t feel good about, even though the number felt good. As an entrepreneur, you might be at the end of your rope and you’re getting diluted off the cap table. You know it’s going to suck or you’re just tired. Maybe you’re ready to go work for somebody else. There are also personal reasons, like you’re not spending enough time with your spouse or kids. And there are board member and investor expectations, and there’s a lot of pressure that I think goes unnoticed and unrecognized. Look at the number of new businesses that start on an annual basis and the percentage that reach different milestones. Every milestone is so ridiculously hard to get to. It is an emotional roller coaster and extremely taxing on your personal life. My advice is to reflect on that honestly.

The second thing you need to think about is the fundamental principles of any good business. In no particular order, it’s the total addressable market, the team and the product. Look at these things with brutal honesty. Don’t lie to yourself and investors and say it’s a $3 billion TAM when it’s a $50 million TAM. You’re never going to sell a unit to every single person out there. It’s not rice. Then there are the people you surround yourself with. One toxic person will bring the whole thing down. And there’s the product. If it’s not easy to buy, easy to use and easy to sell, you’re never going to scale. If you can’t scale, you’re not going to get to these pie-in-the-sky valuations an investor’s willing to pay.

AH: You have experience as an investor, too, which I imagine is helpful.

BM: I can’t say I’ve done as many deals as the team at CI, but I have gotten term sheets from big VCs, and it’s gone well and not well. I’ve been in the market when it was ugly and banks were crashing and everything was underwater and upside down. Nobody wanted to invest in anything new. It was a lousy time. But it gave me a different perspective because when you put your own money in, you think about spending it a lot differently than when you get it from somebody else.

At my last company, at one point I raised almost $80 million in cash, but I was too immature to understand how to watch every penny. I had a mentor who set me straight. I then delivered uncomfortable messages to the team, like how we weren’t going to hire for a certain position. They said, “Why? We have money.” But they appreciated it when it came time to exit, because nobody wants to buy a company that’s printing cash. Not these days. Investors want EBITDA, cash flow, solid operations, thoughtful financial planning…we spent a ton of time on that at Populi. I had a top-notch CFO who was coming off a hiatus after having worked with startups and publicly traded companies, and our COO had done four or five of these companies with me. We had a world-class operational infrastructure. In a startup it’s super, super lucky, but we focused on that from the beginning.

The other thing we did was stay in stealth mode for a year. When I first put money in, and we were the first money, I said this is going to be the money and we should expect to close one deal in a year or more. It took 10 months, but only because the customer came to us and asked us to test the product, and then they wanted to buy it. We got lucky.

My recommendation for other entrepreneurs is to realize that if you’re overselling and underdelivering, you’re in trouble. If you didn’t do a good amount of R&D and customer testing and really get out in the market, you’re going to be in for an ugly surprise. Manage every dollar that comes in because it could be the last dollar you’ll ever get. Drive the company on your own cash flow. A lot of venture mentality is, “Well, if we can raise $10 or $20 million, we don’t need to make money. We can just keep building and innovating.” No. You should try to find a way to get to cash flow breakeven—at least. A lot of entrepreneurs don’t think about that.

AH: Anything else you want to tell our readers?

BM: I grew up in Connecticut. It means a lot to me to see innovation occurring here. I appreciate that every time I’ve had an idea Connecticut Innovations has been there to talk it through and that CI finds ways to get capital out to early-stage companies. They were great partners on this journey.

I want to leave you with my thoughts about what it takes to be an entrepreneur and to have exits, because if you find a model that yields good outcomes, all you have to do is keep running it and refining it. If you do, employees are going to follow you, investors are going to follow you, customers are going to follow you, and markets are going to follow you. If you choose to veer off the entrepreneurial path for a bit, though, something positive will come out of that, too. You don’t always have to be the founder or CEO. It’s OK to get large company experience at a different level. You’ll get a better understanding of what’s on the other side of the wall, which is great, because these are the companies that buy you.

AH: Thanks, Bill. Great stuff.

BM: My pleasure.

CI’s Fund of Funds Spurs Interest

Connecticut Innovations has been investing in high-potential, early-stage companies for decades. Founded in 1989, CI helped launch Alexion Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ: ALXN), Arvinas (NASDAQ: ARVN), Biohaven (NASDAQ: BHVN), Tru Optik and hundreds of other companies, many of which have gone on to generate considerable financial returns for the state. Long recognized for seeding startups and for developing programs to address emerging opportunities for VCs, Connecticut’s venture capital arm has a new tool in its toolbox. Surprisingly, it’s not aimed at entrepreneurs—at least not directly.

Investing in investors

If you’re familiar with CI, you may know that it has historically invested in startups through tools like its flagship Eli Whitney Fund and the Connecticut Bioscience Innovation Fund (CBIF). CI’s new program is different. Rather than seeding startups, the goal of the Fund of Funds (FoF) program is to purchase stakes in other investment vehicles managed by other fund managers who are looking for investment opportunities.

The benefits are numerous. “The fund managers we invest in have deep industry expertise and handle due diligence, the selection process and monitoring, which saves us time and resources,” said Connecticut Innovations CEO Matt McCooe. “Even better, they greatly expand our access to the types of companies we want in our portfolio: those with great management teams, proprietary assets and large, addressable markets. We can watch these companies grow and then invest directly in those with the most potential.”

Like venture investing, investing in other investors requires patience. Indeed, McCooe’s team has been laying the groundwork for CI’s new program by selectively investing in large and small funds over the past five years. To date, CI has committed $30 million to 13 funds, including:

- Acadian Ventures I

- Bullish Ventures II

- C2 Ventures II

- Canaan XII

- Canaan XIII

- Elm Street II

- HighCape II

- HSCM II

- Skyview Ventures

- Tamarack Global

- Vesey Ventures I

- Wheelhouse 360

- 1843 Capital Ventures

Each of the funds has an office in Connecticut or has agreed to open one here. So far, seven funds have invested a total of $75 million in 2o Connecticut companies in deals totaling $900 million. As of last quarter, these investments helped create 430 jobs in Connecticut.

Meet the fund managers

McCooe said that CI seeks to build relationships with experienced VCs with whom its interests align. Kevin Rakin is one such investor. A co-founder and partner at HighCape Capital, a growth equity fund that focuses on life sciences companies, Rakin brings 30 years of experience as an executive and an investor. Before founding HighCape in 2013, Rakin was president of Shire Regenerative Medicine; chairman and CEO of Advanced BioHealing (ABH); an executive-in-residence at venture capital firm Canaan Partners; and co-founder, president and CEO of Genaissance Pharmaceuticals.

CI invested $3 million in Westport-based HighCape, whose portfolio includes several Connecticut companies: New Haven–based Alphina Therapeutics, which licenses technology developed at Yale University to exploit metabolic defects and develop new treatments for cancer; New Haven–based Wellinks, which has developed connected medical devices and technologies to help people living with asthma, COPD and other respiratory conditions; New Haven–based Modifi Bio, a preclinical stage biotech company creating a new class of molecules to selectively kill cancer cells via direct cancer DNA modification; Guilford-based Quantum-Si, a pioneer in next-generation semiconductor chip-based proteomics; and Cybrexa Therapeutics, a New Haven–based oncology-focused platform technology company.

Rakin said CI delivers tremendous value to HighCape. “CI’s involvement makes such a difference. When the state’s venture capital arm endorses and invests in you, it gives an imprimatur of credibility.”

Brent Montgomery is another investor CI is betting on. Like Rakin, Montgomery has a successful track record as both a businessman and an investor. After finding massive success in reality TV—Montgomery’s hit shows include Pawn Stars, Queer Eye and Fixer Upper, among others, and he sold his production company at a $450 million valuation—Montgomery said he realized how much brand-building a camera and some exposure could do for a business. He launched Wheelhouse 360 in 2018 in Stamford to capitalize on that knowledge. The fund invests in lower-middle market consumer businesses and brands it can add value to through content. “Look at what Fixer Upper did for Magnolia; look at Barbie,” he said. “Authentic entertainment content has a magnificent effect on a brand.”

Mongomery describes CI, from which he received a $3 million commitment, as a “thoughtful” partner. “We share deal flow with each other, and they’re good at making introductions. They’re synergy because no one feels like they need to be a hero.”

Bullish is another fund that received $3 million from CI. Like Rakin and Montgomery, Michael Duda, a managing partner at the hybrid consumer investor and branding agency, has had considerable success in business and investing. Bullish was an early investor in Casper, Peloton, Warby Parker and scores of other household-name companies. His fund’s current roster includes Function of Beauty, Hally Hair and Sunday Lawn, to name just a few.

Like the other investors in the FoF program, Duda said CI’s partnership lends credibility to his deals. He also praises CI as “enthusiastic” and “pro-business.”

“CI has a public relations program, it’s got a great intern program, there are diversity and inclusion initiatives, and there’s a women’s investor network that helps get more women involved in investing,” said Duda. “I’m extremely proud to be a part of this community.”

CI plans to allocate another $20 million to its Fund of Funds program over the next two years.

“This Meeting Could Have Been an Email”

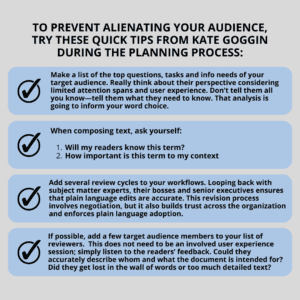

How plain language can strengthen communication—both inside and outside your organization

If your company builds robots for advanced manufacturing or develops novel biotherapeutics to cure rare diseases (or anything similarly complex), you may struggle when trying to describe your work to a non-technical audience. But using plain language is a smart move—and not just because it can help you avoid unnecessary meetings. Kate Goggin, a communications consultant to the federal government whose clients have included the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. State Department, among others, explains why this tool is so beneficial. Even better, she tells us how to use it.

Connecticut Innovations: Thanks for agreeing to share your expertise, Kate! You have extensive experience translating jargon and tech talk into clear writing, but our readers are mostly tech entrepreneurs and investors who often communicate with other technical people. Can plain language benefit them?

Kate Goggin: Absolutely. Plain language is a method or way of writing focused on reader results, so they can:

- Quickly find what they need.

- Understand what they read the first time.

- Use what they read to fulfill their needs.

Those goals are shared by businesses from every industry and sector. It’s a direct way of communicating, so employees spend less time explaining their messages to people, therefore saving time and money. Additionally, plain language, also known as plain English or plain writing, can improve customer service/user experience and increase brand trust.

More business and technical leaders are embracing plain language because they know those benefits quickly translate to bottom line results like increased sales, improved reputation, and decreased complaints. Also, I want to note that plain language writing strengthens internal communication. You know the saying, “this meeting could have been an email.” That’s very true, especially if it was a well-written email. Think about it, people know you first by your writing now. Between COVID and the rise of remote work, chances are high that you will “meet” virtually through your emails, prospectus, or project charter long before you actually meet a hiring manager or board member in person.

CI: Great point! A common misconception is that plain language simply dumbs down communications. Can you set the record straight?

KG: Plain language is not an oversimplification or “dumbing down” of important text. Also, it is not less precise, and it does not leave out necessary technical or legal terms. What it does eliminate, however, is unnecessary complexity and jargon.

I will be the first to agree that jargon is an important tool among peers inside a sector or field. I have worked with diplomats, scientists, lawyers, engineers, and computer experts who must use the same professional terms to establish credibility, compare results, or advance projects. But while jargon can expedite communications between peers, it can frustrate outside readers. Every employee needs to communicate clearly outside of their office, up and down the chain of command. Whether briefing stakeholders, the company president or new employees, plain language methods are the fastest way to communicate with everyone to get the results you want.

CI: Is there ever a case where you wouldn’t recommend plain language?

KG: No, every communication product can include plain language. The body of the document or online content may require using specific terms, acronyms or abbreviations known to the technical audience, but every product will also be read by non-technical audiences.

Typical sections for inserting plain language into a technical document include: the introduction, executive summary, recommendations and conclusions.

Ask any entrepreneur or contractor and they will tell you that often the executive summary is the only section busy decision-makers have time to scan these days. The experts know a well-written summary can be the difference between a funded or unfunded program or a positive or negative review. Technical peers may dive down into the details, but the media, the public or the board of directors will not.

CI: Are there different plain language guidelines for websites, press releases, software manuals, etc., or are the principles largely the same?

KG: Plain language principles are largely the same for different communication products. I train government and business clients, and I recommend the five steps to plain language outlined by the Center for Plain Language.

- Define your audience.

- Structure the content appropriately.

- Write in plain language with everyday words.

- Use information design.

- Review, test and design the content.

I also want to clarify, the plain language writing method is not the same as a style guide, such as the Associated Press style guide. Every organization can write text in plain language and then apply their own style guide or one required for distribution.

CI: Is plain language something you plan for, or is it an editing process after the fact?

KG: You can plan an original communication in plain language, but as you can see from your credit card policy, medical release form or cybersecurity manual, many organizations do not start with a plain language approach. That means there is a growing demand for training as well as editing services.

I encourage businesses to be proactive and improve staff skills now before the company web content, financial data or scientific report is misunderstood. Make clear communications a priority and reap the rewards.

CI: Anything else you want to mention to our readers?

KG: Plain language has become an important tool regarding access to information, citizen rights and a more inclusive culture. Access can include reaching non-native English speakers and people with cognitive disabilities or low literacy skills.

- Many local, state, federal and international organizations and governments now equate access to information as a citizen right, and plain language is the preferred method.

- In a related development, plain language usage is now also associated with ethical behavior because plain language documents help people act on their rights as consumers, patients or voters.

- Corporate America is quickly seeing the benefits of plain language usage to bolster sales, but also to expand access to inclusive programs such as:

- diversity and inclusion programs (and recruiting)

- corporate social responsibility programs (and outreach)

- financial literacy programs (and customer service)

- health literacy programs (and regulatory compliance)

CI: Thanks, Kate! We can’t wait to put your tips to work.

To review Kate Goggin’s List of Quick and Easy Plain Language Resources or Justification Resources for Plain Language Training, click here.

New Fund Seeks Early-Stage Tech Companies Led by Underrepresented Founders

For decades, CI has witnessed the positive change that comes from seeding early-stage companies whose innovations improve lives around the world. Among other breakthroughs, CI-backed companies have cured rare diseases, pioneered lifesaving medical devices, simplified business processes, and more. They’ve also generated healthy returns for the state and high-paying jobs for Connecticut residents. Now, the state’s venture capital arm has a new goal—to prioritize underrepresented founders—and it has earmarked $50 million to make it happen.

Managed by Alison Malloy, managing director of investments at CI and a successful entrepreneur in her own right, the Future Fund will invest from $250,000 to $1.5 million in venture-backable startups with diverse founders and teams that demonstrate significant growth potential. The fund is largely sector agnostic, though Malloy said she is particularly interested in companies focused on fintech, proptech, healthtech, insurtech, AI and consumer packaged goods. The state has a robust ecosystem in these industries, including considerable talent and mature companies, which CI draws upon to accelerate startup growth.

To maximize the state’s return on its investment, the fund will prioritize companies that have customers and proven traction.

Diversity in focus

Diversity in focus

Although CI has always evaluated management team strength as part of its due diligence process, diversity was never a formal consideration. Recognizing that diverse teams produce better outcomes, the Future Fund aims to change that. “Over the past 10 years, there’s been an increase in VC funding for women here in Connecticut, which is a great start, but it’s not enough,” Malloy said. “The fund supports founders who consider themselves underrepresented. That’s the part of the ecosystem the Future Fund is trying to capture.”

“There’s a lot of money out there for founders with great ideas,” Malloy added. “Supporting visionary founders, especially underrepresented founders from diverse backgrounds, will strengthen our innovation ecosystem, lead to additional job opportunities in Connecticut, benefit communities that might not otherwise receive VC funding, and help create generational wealth.”

While the fund is too new to have success stories just yet, the portfolio is quickly growing, including investments in the following companies: 2045 Studio, Dream Payments, Ellis Brooklyn, Hally Hair, Intellihealth and Matrix Rental Solutions. Malloy’s team is also largely focused on building a strong pipeline. “We want to find the next unicorn in Connecticut,” she said. “We’re looking for high-growth, venture-backable companies with disruptive, proven technology, strong traction, and strong moats.”

Fund goals

The goals of the Future Fund, like all CI’s funds, are twofold: To generate a return on investment that CI can then funnel into additional high-potential companies, and to create meaningful jobs in the state. CEO Matt McCooe said he couldn’t think of anyone better to lead the effort. “It’s difficult for any founder to raise money, and it’s especially difficult for first-time founders and for women and minorities,” he said. “You have to search widely to find CEOs of venture-backed companies who have led successful exits in Connecticut. Alison not only was able to raise money, but she also sold her company to a large multinational in 2016. She went through the Springboard Enterprise program; she was Golden Seeds’ first investment and its first exit, and one of AIF’s first investments as well. Two years ago, she co-founded Tidal River to help accredited women investors source and vet deals. Her network is deep and wide, and she’s spent the past seven years helping other underrepresented entrepreneurs. Having her dedicate her time to finding and vetting companies with diverse founders, talent and ideas will mean we’ll soon have a rich portfolio of new companies that can grow quickly, make a global impact and help cement Connecticut’s reputation as a leading tech hub.”

Malloy added, “I know and understand the challenges and the process of fundraising because I went through it myself. CI is ready to provide capital and strategic support, especially introductions to partners in our ecosystem who can help position the startup for acceleration and prepare it for additional funding. We have a strong network of innovators and investors who recognize the positive impact diversity has on outcomes, and we’re excited to help launch the next generation of great companies in Connecticut.”

Interested entrepreneurs can apply on CI’s website.