Serial entrepreneur Bill Moschella’s company, Populi, was acquired by Definitive Healthcare for $52 million just three years after inception. Here, he tells writer Amy Hourigan how the company got its start, why he decided to sell, and the mistakes he hopes other entrepreneurs will avoid.

Amy Hourigan: Thanks for talking with me, Bill. You went to school for music. How did you find yourself at the helm of a digital health company?

Bill Moschella: I went to a couple of different music schools to study 20th-century music theory and composition, which is technical, math-type stuff, but since I can read music, I also played in multiple bands. It was fun, but I wasn’t making any money. Sometime in the ’90s I bought a digital recording studio and realized I could make money recording bands, which, at the time, was kind of groundbreaking. I got really into it and started connecting with people in tech support—back then it was mostly by telephone—asking questions and learning how to fix things while providing feedback about the product. This was the buildup to everything I would later do with software.

Eventually, someone at the company connected me with someone else who they thought would be interested in learning how I was using their software. I got free access to their application and started using it to transfer music by converting digital stored music into digital shared music. This was during the early days of Napster and music sharing. I found ways to reduce file size and maintain quality.

AH: That’s impressive for someone who is self-taught.

BM: Well, I’m not some genius. I was just spending a lot of time on it. I figured out a bunch of cool hacks and started writing about them. At the time, everything was really slow, but everybody wanted to have these animated splash images on their websites or animations with video or audio. I figured out a way to compress the audio to get the most out of it. The company liked what I was doing and eventually put me in touch with a big publishing company, IDG Publications, which offered me what was at the time for me a lot of money to write about what I was doing. I ended up writing a couple chapters in these large tutorial books for several years.

AH: So digital music led you to programming?

BM: Yes. And then I bumped into somebody who had an advertising business who needed help writing TV commercials and radio jingles. He had an advertising background. And I had a technical background, but it turns out I also had innate sales skills that I didn’t know I had. Early on, when we were doing radio commercials, I had to try to find businesses that had crappy ads, so I would listen to the radio all day long, going through four or five stations at a time. I started learning who was in the rotations. I made a gigantic list on a yellow notepad, and then I went to the Yellow Pages and just started calling companies on the corded wall phone at my parents’ house. When I got meetings with people I said, “Hey, if we make your radio commercial better will you give us the advertising component as well—the strategy, the media buying and planning, etc.?” Besides sales, I found I was good at negotiating rates and understanding where to buy remnant inventory.

AH: So that business took off?

BM: Yes, the business took off and I was able to pay myself. At some point, I wanted to grow even bigger, but my business partner didn’t. This was during the dot-com boom. I knew a few people in the local banking industry, and so I asked them how to buy somebody out. I had no idea how to do it. On their advice I called different boutique banks in in New York, and they were like, “Oh, great, you’re in a technology business. You want a loan?” They gave me a gigantic loan! I couldn’t believe it. My business partner couldn’t believe it. I bought the company from him and quadrupled the size of the business in a very short time.

AH: Sounds like you rode the dot-com boom.

BM: I did. I got into software development, ERP, CRM, digital marketing, email marketing; we became a full-service digital agency. But there were bigger versions of that happening all over. Fortunately, I saw an opportunity to tie it together by doing marketing, digital marketing, marketing automation and downstream ROI analysis. The business evolved into a financial-planning-and-analysis-meets-marketing company. Around 2009 to 2011 there was a big movement around marketing automation, which became demand generation. The space got crowded and I realized I wasn’t going to make it. I couldn’t compete with the really big firms that were popping up.

AH: Is that when you turned to digital health?

BM: Right. At the time, the only industry nobody gave a hoot about was the provider market. So I said all right, let’s turn this into a digital marketing business for providers. And that was the beginning of going out and raising capital, getting into investment banking, dealing with venture capital, having to learn the ropes of running sales, marketing, HR, customer service, accounting and forecasting. I had board members and investors. It was a crash course. It was the best and worst experience I ever had because there were a lot of ups and downs. It was brutal working with sophisticated investors who had a lot of money on the table and realizing just how much more there was to building a successful business. That was 2018. Everything changed from there. [Moschella’s company, Evariant, was acquired in 2020.—ed.]

AH: What a great story! So Populi focuses exclusively on providers?

BM: Yes. There’s a huge business in care delivery and coordination and the whole clinical piece. But then there’s the business of running the business, which not all health systems do as well as maybe they could. Those who are doing it well succeed because they treat the health system as a business.

If these organizations want to grow, they need to make certain decisions so they can stay in business and continue to deliver good care. Populi can help with those decisions. We can help you recruit physicians, understand whom to merge with or acquire, figure out the demand for a particular service or therapy in an outpatient or inpatient setting, whether you should be entering into a value-based contract, etc. There’s lots of data out there.

AH: And you’ve figured out how to put that data to work?

BM: I understand data science and data engineering. That’s where a lot of people fall down.

AH: Your website says that Populi delivers analytics in platforms that your customers actually work in, which seems like a simple concept. Why was no one else doing it?

BM: Why? Well, let’s take a step back. The old-school methodology of delivering this type of service was sending people a bunch of data they could use as they pleased. The other was creating a product people could log in to. Here’s why that doesn’t work. If a provider doesn’t have the money and the resources to manage the data and build their own product, even if they say they want to do it themselves, they’re typically not going to. So that’s a failed approach and you’ll churn that customer. Those who do create the product typically end up saying something like how they can’t get to the answer because they want to double click on your explanation of, say, what you think valve replacement is and look at all the procedure codes and look longitudinally…but we didn’t build it that way. Another failed approach. So I said to my co-founder, Nathan Salmon, “Here’s the deal. Here’s all the data, I know how to get it, here’s the product concepts. I can run the business. But you have to build something that’s plug-and-play from day one. Put your credit card in, get a user license, start using it. It’s got to be very modular and connector-based so people can use the data in Salesforce or Tableau or Google or Amazon.” That’s how we bring analytics to the platforms customers live and work in every day.

Ten years ago, people didn’t know that some of these platforms existed, or if they did, they couldn’t afford them. Now they’re commonplace. What’s not commonplace is an ecosystem in a marketplace where you can tap into these highly complex and HIPAA-compliant analytics with de-identified patient information. You can’t get into the business of data without also being in the business of compliance and security. You also need to understand the controls and policies that are involved with a larger team as it scales. I teed up this opportunity for us to get very narrowly focused on an industry with a key set of business problems and the data that was required to answer those problems, and one that had massive gaps of why they couldn’t consume and use the data. We hyper-focused. That’s why the company was bought so quickly.

AH: How did the deal come about?

BM: It was kind of haphazard. I’m always trying to acquire data assets. One of my angel investors knew I was looking for data and recommended I talk to the corporate dev folks at Definitive. I had an initial call and said, “Hey, can I buy your data?” They said, “Can we buy you?” I told them the company wasn’t for sale, but I said we’d consider it. After one or two meetings they realized acquiring us would be a great way to get the vertical expertise they were looking for, so we kept talking. Those processes aren’t fun, and we had our moments. You always do because it just gets tough. But they were great to work with, which to me was another test. You wonder what it will be like if you disagree on something. They were rational and reasonable and fair. And that’s all you can really ask for.

AH: How did you know it was the right time to sell?

BM: The answer is not just because the price was right. Because, if you’re an entrepreneur, is the price ever really right?

AH: And it’s your baby, right?

BM: Yeah. It’s your baby, and you wouldn’t be an entrepreneur if you didn’t think that no matter what number someone put in front of you that you couldn’t get more. You have your good and evil conscience speaking to you. “Don’t take it. You can do better.” And then there’s the other part that’s like, “Dude, go do something else.” Maybe there’s also a VC whispering in your ear about the returns.

We didn’t have a lot of investors or board members at Populi. It was Nathan and me, so it was an easy conversation. We just sat down and talked about what we wanted out of life and what a good outcome would look like, and not just in terms of money. There were three or four things that were important to us.

I knew that the founder and the chairman of Definitive were good people and experienced leaders who know healthcare. I was able to let my business partner know that these people are ethical and they’ve run companies we would enjoy working with and for. That was the first opening of the door.

The second had to do with our employees. I’ve been part of a handful of companies where the employees got screwed. The story goes something like this: You have a great idea. Maybe you’re a single entrepreneur, maybe you’ve got a partner. At some point your cost basis common stock, which is fantastic, it’s got nothing but upside. It starts getting stack ranked and venture capital comes in and then there are notes and Series A, B and C rounds and different preferences and waterfall payouts and strike prices and all sorts of complicated stuff. Most people don’t understand what they’re getting into. They could receive an on-paper value of a whole lot of stock. But what they may not know is what it will take to get over the strike price. And then how much value is going to be over that? And are we going to hit different preference levels? Is anybody going to get paid at all, including the founders?

I’ve been in situations where—and this is just capitalism—you couldn’t have gotten to where you did if you didn’t take money. So how do you manage and negotiate capital? A lot of people don’t understand it, so they get taken advantage of. Even if you know what you’re doing, the market demands what it demands at any given point in time. If valuations are down and you need money, you’re in a rough spot. You could be in a down round, you could be in a flat round, you could be in a decent round, but you could be accepting terms that might not be all that great. And eventually there’s voting and preference and waterfall and payout. And there’s what happens when you actually sell the company. I’ve seen some awesome numbers on the top that yield zero or negative for employees because the sale price in this common stock price is underneath the strike price they were given. These situations have put large groups of people I’ve known in a lousy position. And then as they go on to a new company, there are economies of scale and integration exercises.

It’s just business, but having had those experiences and having brought a lot of people into the company where the majority of the capital came from my wife and me and a handful of folks like Connecticut Innovations, who I have a great amount of respect for, and Millennium out of New York, and a couple of angels who brought a lot of value to the table due to their industry expertise, we were able to have a very open, transparent conversation about what we were going to do and how we would go about it. We converted nothing to stock. Everything was in a convertible note. That meant the control stayed with Nathan and me the entire time. I treated every note holder as a board member, though. I asked for their input. There was a lot of conversation. The investors had to be taken care of because we all stepped up and put money in, and I was crystal clear that the employees needed to be taken care of as well. If the acquirer says investors are going to get paid but we’re going to kick the tires on everybody else, the answer’s no. Everybody’s got to come over minus a few folks on the HR and finance side who we’d already talked to.

We were only interested in selling to the right company with the right leaders who had the right mindset and vision for the company. Definitive acquired us because they needed product and more subject matter expertise. We needed scale. But we already held a lot of the same values and principles. It was just a cool culture we were joining, which isn’t usually what happens.

AH: How long did the process take?

BM: Well, Definitive had to go through their due diligence, which isn’t easy. In fact, with a company like ours, it’s harder because there are more unknowns—I don’t have 10 years of historicals. There was a leap of faith on both sides. The process took six or seven months.

AH: Do you have advice for other founders who are considering an exit? Sounds like you have learned some lessons over the years.

BM: Yeah, I’ve had a couple exits. Some were anticlimactic. Some I didn’t feel good about, even though the number felt good. As an entrepreneur, you might be at the end of your rope and you’re getting diluted off the cap table. You know it’s going to suck or you’re just tired. Maybe you’re ready to go work for somebody else. There are also personal reasons, like you’re not spending enough time with your spouse or kids. And there are board member and investor expectations, and there’s a lot of pressure that I think goes unnoticed and unrecognized. Look at the number of new businesses that start on an annual basis and the percentage that reach different milestones. Every milestone is so ridiculously hard to get to. It is an emotional roller coaster and extremely taxing on your personal life. My advice is to reflect on that honestly.

The second thing you need to think about is the fundamental principles of any good business. In no particular order, it’s the total addressable market, the team and the product. Look at these things with brutal honesty. Don’t lie to yourself and investors and say it’s a $3 billion TAM when it’s a $50 million TAM. You’re never going to sell a unit to every single person out there. It’s not rice. Then there are the people you surround yourself with. One toxic person will bring the whole thing down. And there’s the product. If it’s not easy to buy, easy to use and easy to sell, you’re never going to scale. If you can’t scale, you’re not going to get to these pie-in-the-sky valuations an investor’s willing to pay.

AH: You have experience as an investor, too, which I imagine is helpful.

BM: I can’t say I’ve done as many deals as the team at CI, but I have gotten term sheets from big VCs, and it’s gone well and not well. I’ve been in the market when it was ugly and banks were crashing and everything was underwater and upside down. Nobody wanted to invest in anything new. It was a lousy time. But it gave me a different perspective because when you put your own money in, you think about spending it a lot differently than when you get it from somebody else.

At my last company, at one point I raised almost $80 million in cash, but I was too immature to understand how to watch every penny. I had a mentor who set me straight. I then delivered uncomfortable messages to the team, like how we weren’t going to hire for a certain position. They said, “Why? We have money.” But they appreciated it when it came time to exit, because nobody wants to buy a company that’s printing cash. Not these days. Investors want EBITDA, cash flow, solid operations, thoughtful financial planning…we spent a ton of time on that at Populi. I had a top-notch CFO who was coming off a hiatus after having worked with startups and publicly traded companies, and our COO had done four or five of these companies with me. We had a world-class operational infrastructure. In a startup it’s super, super lucky, but we focused on that from the beginning.

The other thing we did was stay in stealth mode for a year. When I first put money in, and we were the first money, I said this is going to be the money and we should expect to close one deal in a year or more. It took 10 months, but only because the customer came to us and asked us to test the product, and then they wanted to buy it. We got lucky.

My recommendation for other entrepreneurs is to realize that if you’re overselling and underdelivering, you’re in trouble. If you didn’t do a good amount of R&D and customer testing and really get out in the market, you’re going to be in for an ugly surprise. Manage every dollar that comes in because it could be the last dollar you’ll ever get. Drive the company on your own cash flow. A lot of venture mentality is, “Well, if we can raise $10 or $20 million, we don’t need to make money. We can just keep building and innovating.” No. You should try to find a way to get to cash flow breakeven—at least. A lot of entrepreneurs don’t think about that.

AH: Anything else you want to tell our readers?

BM: I grew up in Connecticut. It means a lot to me to see innovation occurring here. I appreciate that every time I’ve had an idea Connecticut Innovations has been there to talk it through and that CI finds ways to get capital out to early-stage companies. They were great partners on this journey.

I want to leave you with my thoughts about what it takes to be an entrepreneur and to have exits, because if you find a model that yields good outcomes, all you have to do is keep running it and refining it. If you do, employees are going to follow you, investors are going to follow you, customers are going to follow you, and markets are going to follow you. If you choose to veer off the entrepreneurial path for a bit, though, something positive will come out of that, too. You don’t always have to be the founder or CEO. It’s OK to get large company experience at a different level. You’ll get a better understanding of what’s on the other side of the wall, which is great, because these are the companies that buy you.

AH: Thanks, Bill. Great stuff.

BM: My pleasure.

Managed by Konstantine Drakonakis, P.E., an entrepreneur and venture partner who focuses on climate and adaption technology, the fund will invest anywhere from $250,000 to $5 million in a wide range of companies. Its goal: to advance green technology and green jobs, and to support Governor Lamont’s commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. Drakonakis is particularly interested in technologies that address the circular economy, electric vehicles, advanced materials, and mobility apps. Fuel cells, which he says have applications for long-haul trucking, are also a target, as are technologies related to hydrogen, waste and sustainability, and energy and water.

Managed by Konstantine Drakonakis, P.E., an entrepreneur and venture partner who focuses on climate and adaption technology, the fund will invest anywhere from $250,000 to $5 million in a wide range of companies. Its goal: to advance green technology and green jobs, and to support Governor Lamont’s commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. Drakonakis is particularly interested in technologies that address the circular economy, electric vehicles, advanced materials, and mobility apps. Fuel cells, which he says have applications for long-haul trucking, are also a target, as are technologies related to hydrogen, waste and sustainability, and energy and water.

The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Achieving Your Wildly Important Goals by Chris McChesney

The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Achieving Your Wildly Important Goals by Chris McChesney The 5 Second Rule: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday Courage by Mel Robbins

The 5 Second Rule: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday Courage by Mel Robbins The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey The Art of Non-Conformity: Set Your Own Rules, Live the Life You Want, and Change the World by Chris Gillebeau

The Art of Non-Conformity: Set Your Own Rules, Live the Life You Want, and Change the World by Chris Gillebeau Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James Clear

Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James Clear Rich Dad’s Cashflow Quadrant: Guide to Financial Freedom by Robert T. Kiyosaki

Rich Dad’s Cashflow Quadrant: Guide to Financial Freedom by Robert T. Kiyosaki Fierce Conversations: Achieving Success at Work and in Life, One Conversation at a Time by Susan Scott

Fierce Conversations: Achieving Success at Work and in Life, One Conversation at a Time by Susan Scott First, Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently, from Gallup

First, Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently, from Gallup Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman

Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals by Oliver Burkeman The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers by Ben Horowitz

The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers by Ben Horowitz Humor, Seriously: Why Humor Is a Secret Weapon in Business and Life by Jennifer Aaker and Naomi Bagdonas

Humor, Seriously: Why Humor Is a Secret Weapon in Business and Life by Jennifer Aaker and Naomi Bagdonas Hyper Sales Growth: Street-Proven Systems and Processes. How to Grow Quickly and Profitably by Jack Daly

Hyper Sales Growth: Street-Proven Systems and Processes. How to Grow Quickly and Profitably by Jack Daly Killing Sacred Cows: Overcoming the Financial Myths That Are Destroying Your Prosperity, by Garrett B. Gunderson

Killing Sacred Cows: Overcoming the Financial Myths That Are Destroying Your Prosperity, by Garrett B. Gunderson Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t by Simon Sinek

Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t by Simon Sinek The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses by Eric Reis

The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses by Eric Reis Mastering Inbound Marketing: Your Complete Guide to Building a Results-Driven Inbound Strategy by Elyse Flynn Meyer

Mastering Inbound Marketing: Your Complete Guide to Building a Results-Driven Inbound Strategy by Elyse Flynn Meyer Mentor to Millions: Secrets of Success in Business, Relationships, and Beyond by Kevin Harrington and Mark Timm

Mentor to Millions: Secrets of Success in Business, Relationships, and Beyond by Kevin Harrington and Mark Timm Never Lose a Customer Again: Turn Any Sale into Lifelong Loyalty in 100 Days by Joey Coleman

Never Lose a Customer Again: Turn Any Sale into Lifelong Loyalty in 100 Days by Joey Coleman On Becoming a Leader by Warren Bennis

On Becoming a Leader by Warren Bennis The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale

The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy by Micah Zenko

Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy by Micah Zenko Remote: Office Not Required by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson

Remote: Office Not Required by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert T. Kiyosaki Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike by Phil Knight

Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike by Phil Knight Social Engineering: The Science of Human Hacking by Christopher Hadnagy

Social Engineering: The Science of Human Hacking by Christopher Hadnagy Strengths Based Leadership: Great Leaders, Teams, and Why People Follow by Tom Rath and Barry Conchie

Strengths Based Leadership: Great Leaders, Teams, and Why People Follow by Tom Rath and Barry Conchie Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman Trillion Dollar Coach: The Leadership Playbook of Silicon Valley’s Bill Campbell by Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg and Alan Eagle

Trillion Dollar Coach: The Leadership Playbook of Silicon Valley’s Bill Campbell by Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg and Alan Eagle Who Moved My Cheese by Spencer Johnson

Who Moved My Cheese by Spencer Johnson

Cleantech Startups Are the MVPs of CI’s Newest Fund

Cleantech Startups Are the MVPs of CI’s Newest Fund  Konstantine Drakonakis: You’re right. CI has been investing in cleantech for years. We have several companies in our portfolio that are focused on high-potential innovations like better battery storage, fuel cells and clean financing. This new fund is timely, though, given the environment—both literally and figuratively. We need to do more to address climate change now, so that future generations can thrive in a healthy and stable environment. We also want to support Governor Lamont, who is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 and is committed to creating a climate-tech-driven economy. There are funds available to help us with these efforts through President Biden’s American Rescue Plan. CI applied and earmarked $50 million for climate tech deals through its new Climate Fund.

Konstantine Drakonakis: You’re right. CI has been investing in cleantech for years. We have several companies in our portfolio that are focused on high-potential innovations like better battery storage, fuel cells and clean financing. This new fund is timely, though, given the environment—both literally and figuratively. We need to do more to address climate change now, so that future generations can thrive in a healthy and stable environment. We also want to support Governor Lamont, who is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 and is committed to creating a climate-tech-driven economy. There are funds available to help us with these efforts through President Biden’s American Rescue Plan. CI applied and earmarked $50 million for climate tech deals through its new Climate Fund. Alex Waldron Joined a Team Set on Improving the Lives of the Millions of Americans Living with COPD. Here’s How It’s Going.

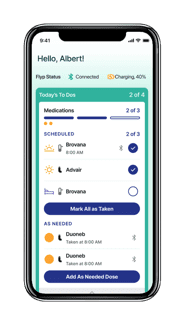

Alex Waldron Joined a Team Set on Improving the Lives of the Millions of Americans Living with COPD. Here’s How It’s Going.

Dr. Reid Waldman:

Dr. Reid Waldman: